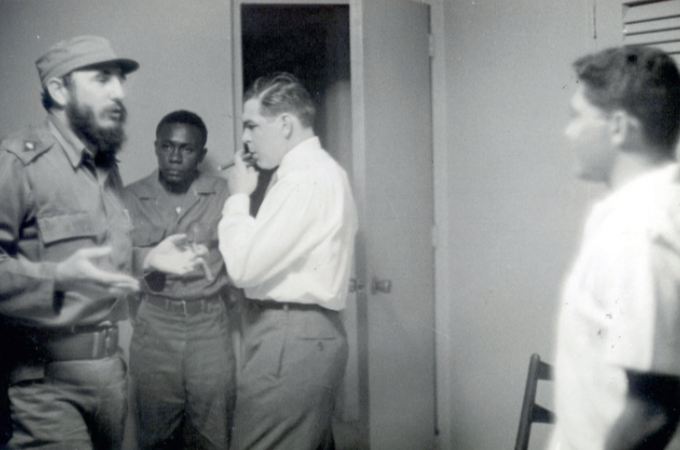

Pictured: Dreke, with Fidel and Che. Photo: Granma Archive

Autor: Laura Mercedes Giráldez | internet@granma.cu

From April to November 1965, Victor Dreke and Che supported the Congolese patriots (from Congo) in their struggle against the government of Moise Tshombe.

A “rebellious little black” who was born on a dirt floor in Sagua la Grande, who had studied with great effort, divided a bread cloth – many years later – into 17 pieces, and distributed them among his classmates.

To cut the pieces – identical, as if they were brothers – he measured the thickness with his finger. One mistake, and someone would go without food.

The last two pieces were for him and his boss, the one who had entrusted him with this “mission”, the one who always wanted to know if there was enough food for everyone, the one who was never the first to take a bite, the one who asked his men to eat the same as the Congolese fighters they were helping at the time in their independence process against the government of Moise Tshombe. the one who admired and respected Fidel.

About his relationship with Commander Ernesto Che Guevara, Víctor Dreke was kind enough to talk with Granma, especially about the months in which they remained on an internationalist mission in the Congo.

Since the departure from the island, for the first Cubans who would fulfill the commitment requested by the Congolese patriots, the one who was in front of them was that “unruly little black,” as he describes himself. In addition, they were unaware of Che’s presence in that land. “I didn’t have a beard, I was changed,” he recalls. The Cuban secret services had taken it upon themselves to change his image.

Thus, without presenting himself with his real identity, to the guerrillas of the Greater Antilles who fought in those African lands from April to November 1965, “he, in his own handwriting, took their names and surnames, the diseases they suffered, data about their families, and right there he gave them a pseudonym, who decided that they should be numbers.”

Moya was the nickname that Dreke – really the second in command – assumed in that epic. While the natives called Commander Guevara Dr. Tatu, and treated him with affection, because in the middle of the war he attended to the sick and shared his medicines with them, he recalls.

And the fact is that Che made solidarity, help, daily practices, which flowed in him with complete naturalness. Dreke knew this well, who assures that, “when you accompany a man in danger, in difficult situations, in war, you really know how much he is worth and who he really is“. He was very close to the hero of the beret and the star.

I had known him since once, when he was wounded and lying in a hammock made of a sack of sugar, he heard a firm voice that asked who was in front of the camp. He was looking for a typewriter. “He wrote every day.” He approached him, worried about his state of health. No one would break the link between those Quixotes.

Later, in African lands, they learned that the First Central Committee of the Communist Party of Cuba had been constituted. Upon hearing the news, Che called him and said: “Moya, now you are my boss, you were appointed a member of the Central Committee.” There can be no doubt about his convictions.

There too, “after the death of his mother, I saw him with his head down, but strong. He did not bring his sorrow to the troops.” He saw him sad, sick with malaria, worried about the liberation of other peoples, he saw him stand up at decisive moments, be an example.

“He was a strategist of guerrilla warfare. He fought and knew how to die defending his cause, that must be respected,” he says.

At the time the death of the Heroic Guerrilla was known, Dreke was not with him. He was in Guinea Bissau, fulfilling another internationalist mission. There was pain, yes. A big man was saying goodbye to life. However, it was the necessary impetus to continue with that task they now had. Thus, “in his tribute,” he emphasizes, “we decreed the operation Che has not died, and we attacked barracks for 15 days.”

For Víctor Dreke –Moya– the willingness to do in favor of others was always in his veins. But together with Che that conviction grew. “He was the true example of an internationalist,” he says.